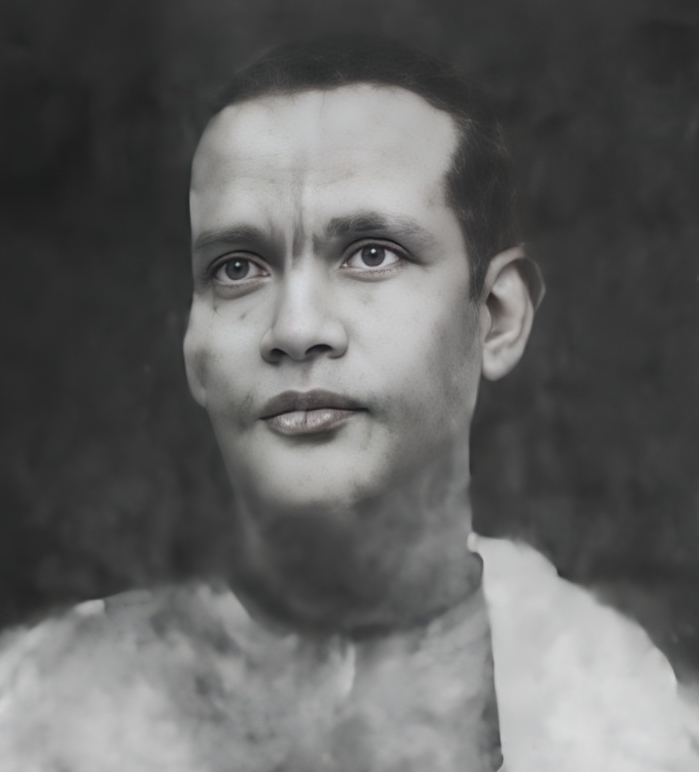

Father of Odia Cinema : Mohana Sundara Deba Goswami

Early Life and Cultural Roots

Father Of The Odia Cinema was born on 8 August 1892, Mohana Sundara Deba Goswami was an exceptional Odissi musician, poet, composer, and exponent of traditional Rahasa or Rasa, a theatrical dance-drama centered on the divine romance of Radha and Krishna. He emerged not only as a guru in spiritual and cultural performance but also as a trailblazer in early Odia-language cinema. His deep immersion in classical Odissi music—ranging from Chhanda, Champu, Kirtana, Bhajana to Janana—earned him reverence across Odisha. His gramophone recordings under His Master’s Voice and broadcasts on All India Radio made him a household name.

Preserving the Rasa Tradition

Determined to keep the Rahasa tradition alive, Goswami formed a dedicated Rasa troupe that toured not only across Odisha but also to other parts of India. Blending culture with spiritualism, his troupe would travel for six to seven months a year, presenting performances based on Krushna Leela—the divine acts of Krishna—drawn from Jayadev’s Gita Govinda. This 12th-century Sanskrit poem, originally composed for night-time dance rituals at the Jagannatha Temple, gained immense popularity and became central to Indian classical dance, music, and temple worship.

A Multifaceted Visionary

Goswami’s artistic range was extraordinary—he was a director, screenwriter, singer, musician, and actor, excelling in each role. He poured his creative energy into shaping the foundation of Odia cinema, earning recognition as the father and doyen of Odia films. His leadership, vision, and artistic sensibility brought sophistication and spiritual depth to every project he undertook.

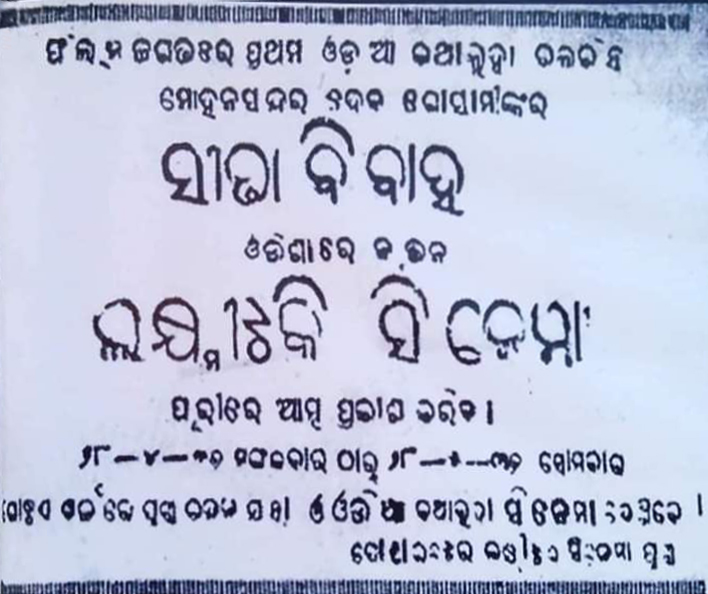

Birth of Odia Cinema: Sita Bibaha (1936)

In 1936, shortly after Orissa became a separate province, Goswami took a monumental step by directing the first Odia-language film, Sita Bibaha, which premiered on 28 April 1936. Inspired by Bengali talkies and supported by the Jagannath Club in Puri, he transformed a stage play by Kamapal Mishra into a full-length feature film. Drawing from his expertise in Rasa Nritya, Goswami brought to life the story of Lord Rama and Sita’s marriage, a key episode from the Ramayana.

The Father of Odia Cinema : Challenges in Production and Exhibition

The film was shot over three to four months at the Kali Films studio in Calcutta, with a production cost of around ₹30,000—a considerable investment at the time. Music was composed by Mari Charan Mohanty, and the two-hour-long film included eleven songs, blending traditional melodies with theatrical storytelling.

Given the scarcity of permanent cinema halls, the film was exhibited in makeshift venues across Cuttack, Puri, Berhampur, and Sambalpur, often through Remeria Touring Cinema—a mobile setup that traveled with projectors and equipment to erect temporary theatres in towns and cities.

Critical Acclaim and Tragic Outcome

Though Sita Bibaha received critical acclaim and was appreciated by audiences for its originality and devotion, it failed commercially. The financial backers faced heavy losses, resulting in the closure of Kali Films. To add to the tragedy, legal disputes prevented Goswami from receiving any payment for his work.

Despite his pioneering contributions, Mohana Sundara Deba Goswami spent his final years in poverty and obscurity, passing away at the young age of 46 on 11 January 1948. His groundbreaking work went unrecognised during his lifetime, but history now remembers him as a visionary artist who laid the very foundations of Odia cinema and rejuvenated Odisha’s classical performing arts.

The Father of Odia Cinema : A Forgotten Pioneer

Despite his monumental contributions to Odia culture and cinema, Mohana Sundara Deba Goswami remains a largely forgotten figure. His pioneering film, Sita Bibaha, which marked the birth of the Odia film industry, has not been restored or digitized—a tragic loss for both our cinematic and cultural heritage.

As usual, we Odias have failed to preserve the legacy of one of our own. Even today, many do not even know his name, nor understand his role in shaping Odisha’s artistic identity.

We often say, “If I survive, my father’s name survives.” But this belief has replaced genuine pride with passive memory. There is no active pride in our language or history—just words and more words, spoken without action, remembrance, or responsibility.

If we are to honor Goswami’s legacy, we must do more than speak of the past—we must preserve it, protect it, and pass it on.